How I Structured The Lost Hero (and Kept It Honest)

People think books arrive fully formed.

Mine began as pencil scribbles, coffee rings, and a tangle of memories. The trick wasn’t finding the story, it was organising it so the heart hit first.

The Two-Thread Spine

I built The Lost Hero on a simple, sturdy frame:

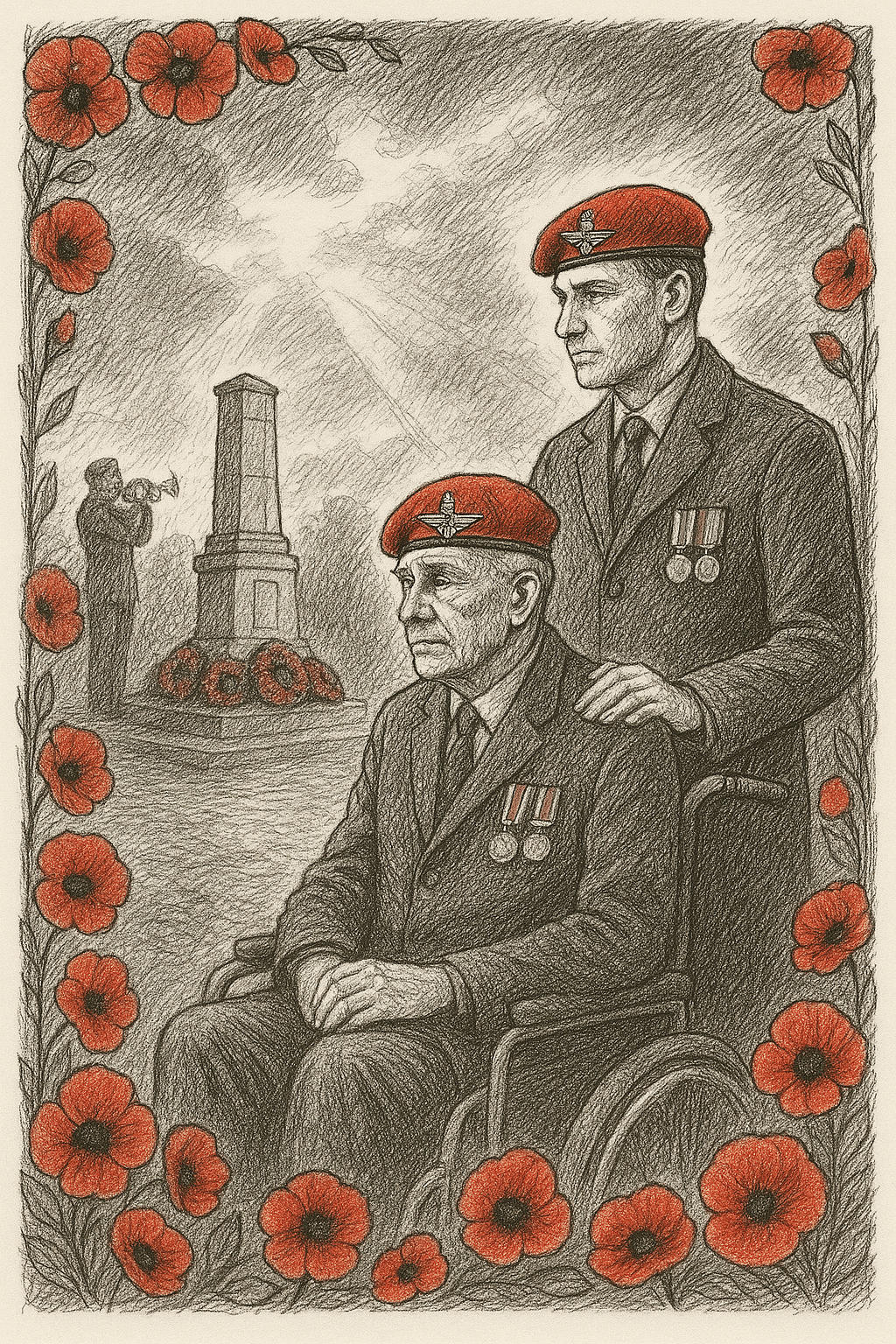

Present Day (Bedside): Michael sits with his dad, William, whose memory is slipping, and reads to him. This is the heartbeat, quiet rooms, soft light, the weight of what’s been lost and what still remains. Service Years (Flashbacks): Each reading session opens a window to William’s past: the jungle grit of Plaman Mapu (1965), the tension of Belfast patrols (early ’70s), and the bitter winds of ’82. These scenes carry the noise, pace, and peril.

The two threads “talk” to each other. A line Michael reads becomes the cut to a past moment; a detail in the flashback echoes back in the room, a gesture, a phrase, a smell of polish, and we feel memory stitching itself together.

The Beat Pattern That Kept Me Honest

To stop the story from drifting, I used a repeating rhythm:

Quiet: Bedside chapter, truths, tenderness, the cost of time.

Contact: Flashback chapter, boots, webbing, SLR weight, decisions under pressure.

Return: Brief present-day reflection, what that memory means now.

That cadence gave readers time to breathe without losing momentum. It’s also why I kept the book tight, about 28–29k words. Every scene had to earn its place.

My “Map, Not a Maze”

I sketched a one-page outline with three movements:

Act I – Set the Promise: Introduce the reading ritual and the debt of remembrance. Hint at the key chapters of William’s service.

Act II – Test the Bond: Raise the stakes, harder memories, the risk of forgetting, the pressure on Michael to keep reading.

Act III – Keep the Light: Bring the story home with meaning, not melodrama, service honoured, love made visible.

I wrote chapter cards (A6 index cards in a shoebox—proper old-school): setting, objective, one vivid sensory detail, and the emotional turn of the scene. If a card didn’t have a turn, it didn’t make the cut.

Rules I Wrote On a Post-it Above My Desk

Truth over tricks. No flashy timelines that confuse more than they clarify. No stolen valour. If a feat felt implausible, it was out. Respect the families. The ones waiting at home are part of every mission. Authenticity isn’t seasoning, it’s the stew. Cam cream, wet socks, basha lines, NAAFI brews, SLR heft, written like someone who’s lived it.

Keeping the Details Tight

I pressure-tested chapters against memory and lived practice: how bergens pull on the shoulders, how a trench smells after rain, how humour cuts through fear, how orders sound when they’re barked, not typed. I leaned on conversations with veterans (from my own era and older), then blended that feel into fiction so it honoured truth without naming names.

Tools & Tactics

Notebook first. Pencil drafts to avoid over-editing too early. Chapter cards. One card = one purpose. Chapter clocks. I noted estimated reading time per chapter to keep pace snappy. Language pass. British military terms throughout, no Americanisms creeping in. Read-aloud test. If dialogue clanged in the ear, it got rewritten. And having to create a book that anyone can understand and not fill it with military jargon.

What Got Cut (and Why)

Extra kit dumps and technical digressions, great for a manual, death for pace. Repeated patrol beats. One sharp scene says more than five similar ones. Anything that flattered the author. The story belongs to William and Michael.

Why This Structure Serves the Heart

The bedside thread carries love; the flashbacks carry cost. Woven together, they say: service never truly ends, and remembrance is a living act. That’s the promise I made to the reader, and to the people who inspired the book.

—

Read the book: The Lost Hero is out now on Kindle (link in my bio/profile).

Tomorrow’s post: “Character Deep Dive—William & Michael Clarke (and what each is really fighting for).”

Leave a comment